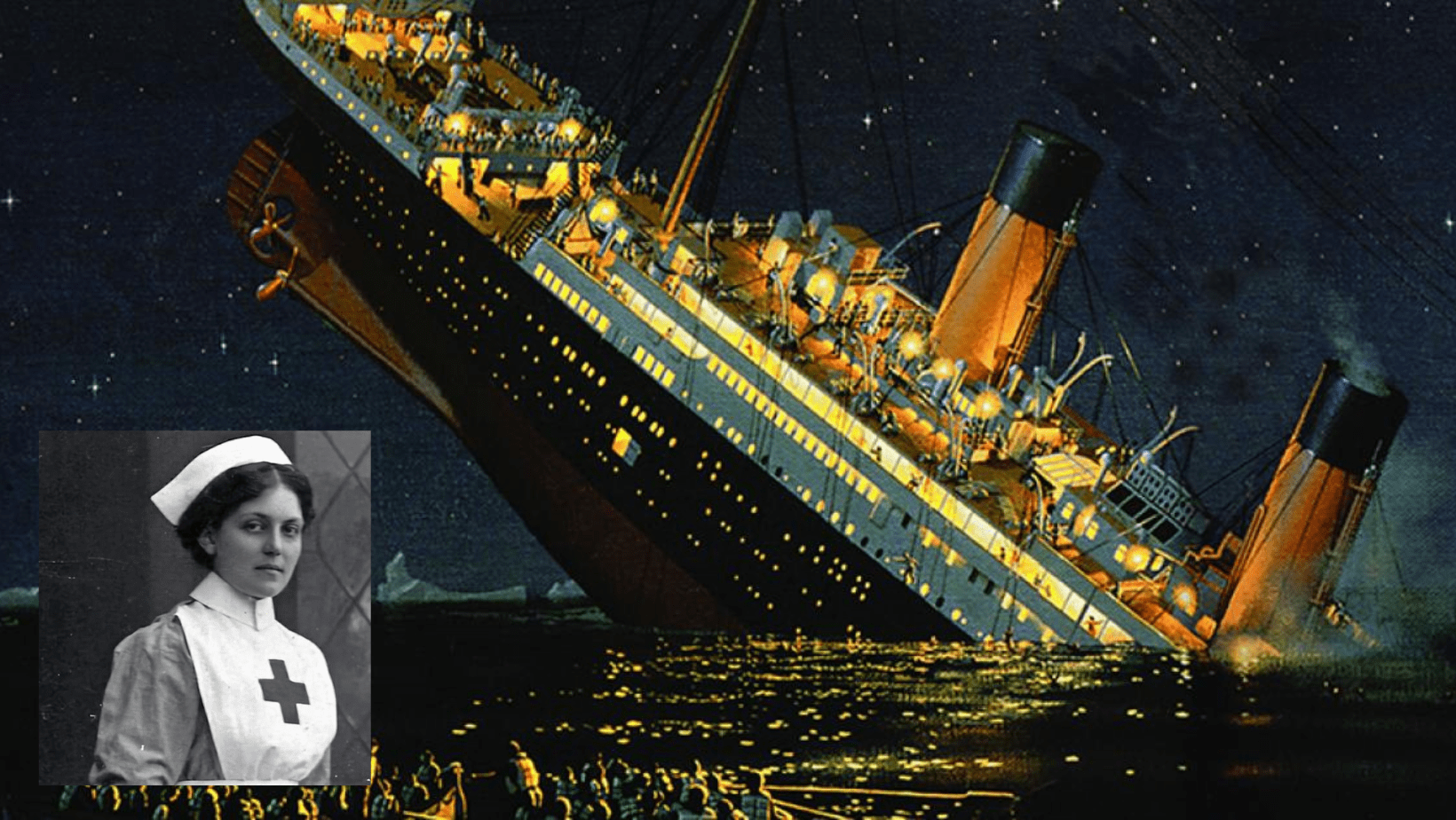

Violet Jessop has been referred to as the queen of sinking ships. During the 1910s, she was on board three of the world’s most famous ships that sank, yet she survived to tell the tale on both occasions. There we examine the incredible story of a woman who was both very unfortunate and extremely lucky in her Experiences.

Early life

Jessop was born on 1887 and was the youngest daughter born to an Irish couple who lived in Argentina. Her childhood was filled with difficulties. Three of her brothers passed away when they were young, and Jessop herself was diagnosed with tuberculosis. After her father passed away, Jessop’s mother accompanied her six children who survived to England and secured a position as a stewardess aboard an ocean vessel. Jessop was too sick to work, but it was the responsibility of Violet, a 21-year-old Violet to care for her family.

Jessop took on the same job as her mother and ended up becoming Stewardess at the White Star Line, a famous shipping company that carried passengers and cargo over the Atlantic. Jessop was employed in first-class cabins, taking care of passengers’ various and varied requirements. She made beds, served breakfast buffets, washed bathrooms, set up flowers, and did the errands. It was “no aspect of service that was not her or her colleagues’ responsibility,” John Maxtone-Graham writes in the editor of Jessop’s autobiography, Titanic Survivor.

RMS Olympic

In 1911, Jessop started her career as a stewardess on the White Star liner RMS Olympic. Olympic was a luxurious ship that was the largest civilian liner at that time. Jessop was aboard on September 20, 1911, when Olympic was en route to Southampton and hit one of the British battleship, HMS Hawke. Despite the damage, there were no deaths and it could still return to its port without sinking. Jessop did not discuss the accident when writing her personal memoirs. She continued working for Olympic until April 1912, after which she was transferred to the sister ship Titanic.

RMS Titanic

A couple of years later, the White Star Line was looking for crew members to serve those who were VIPs on the Titanic. Violet accepted a position on the “unsinkable” ship. Jessop embarked on the RMS Titanic as a stewardess on April 10, 1912, at the age of 24. A few days later, on April 14, it collided with an iceberg in the North Atlantic and sank about two hours and forty-five minutes following the collision.

Jessop wrote in her memoirs the time she was escorted to deck as an example of what to do for those who were not English speakers and did not follow the directions they were given. She was watching as the lifeboats were loaded. She was later escorted to lifeboat 16, and while the vessel was being lowered, the Titanic’s officers handed her a baby to take care of.

“I was ordered up on deck. Calmly, passengers strolled about. I stood at the bulkhead with the other stewardesses, watching the women cling to their husbands before being put into the boats with their children. Sometime after, a ship’s officer ordered us into the boat first to show some women it was safe,” she wrote in her memoir.

In the lifeboat, Violet was handed a newborn to take care of. A few hours later, Jessop was onboard the RMS Carpathia, the vessel that rescued the Titanic survivors in a dramatic search and rescue operation. While she was at the top of the deck freezing and dazed woman rushed towards her and pulled the baby out of her arms. “I did wonder why,” Jessop writes, “whoever its mother might be, she had not expressed one word of gratitude for her baby’s life.”

HMHS Britannic

Jessop did not want to go back to her life at sea in the aftermath of the catastrophe. However, she was forced to do so as it was because she “needed the work.” After the start of World War I, she was a nurse on HMHS Britannic, which was transformed into a hospital ship during the conflict. Jessop was aboard on November 21, 1916, at the time that the Britannic was struck by the surface of a German mine, and then began to sink quickly to the Aegean Sea.

Jessop was instructed to get off in a lifeboat alongside a few of her crewmates. They were engaged with a horrifying scene once they got to the water. The propellers on the ship were still moving through the water, sucking boats and passengers as well into the blades. Although she had spent a lot of time on the sea, Jessop did not know how to swim. However, she couldn’t afford to remain on the vessel. She grabbed her lifebelt and jumped into the water. After she was back on the surface, her head was smacking against with the vessel’s keel. “My brain shook like a solid body in a bottle of liquid,” she writes.

Jessop grasped a lifebelt spare that was floating in the water and was able to hold for a while until one of Britannic’s motorboats brought her to shore. Jessop was able to survive another sea-related disaster; however, the blow to her skull could be a source of headaches for years.

After retirement

Despite her tumultuous times at sea, Jessop continued to work on passenger service on large vessels. She joined with the White Star Line after the war and then signed to a different company called Red Star Line that took Jessop all over the world for five voyages. After a few years of clerical positions on the shore, she went back to the sea for two years, aboard cruises with the Royal Mail Line’s cruises across South America. She resigned from her illustrious profession in 1950, when she was 63 years old, and then moved to the countryside.

Jessop spent her final years in the land she had cultivated and tended to her beautiful backyard, raising chickens for eggs to earn an extra income. She passed away from congestive heart disease at 85 in 1971.