Five decades ago, more than 80 orcas were captured by a group from Whidbey Island in Washington. They took young orcas and separated them from their mothers using explosives, nets, sticks and boats. According to an account of that day, the whales’ human-like sounds haunted locals.

Six baby whales were taken from Penn Cove that day and sold to marine park owners. Many didn’t survive a year in captivity. Only one is still alive after being captured and sold.

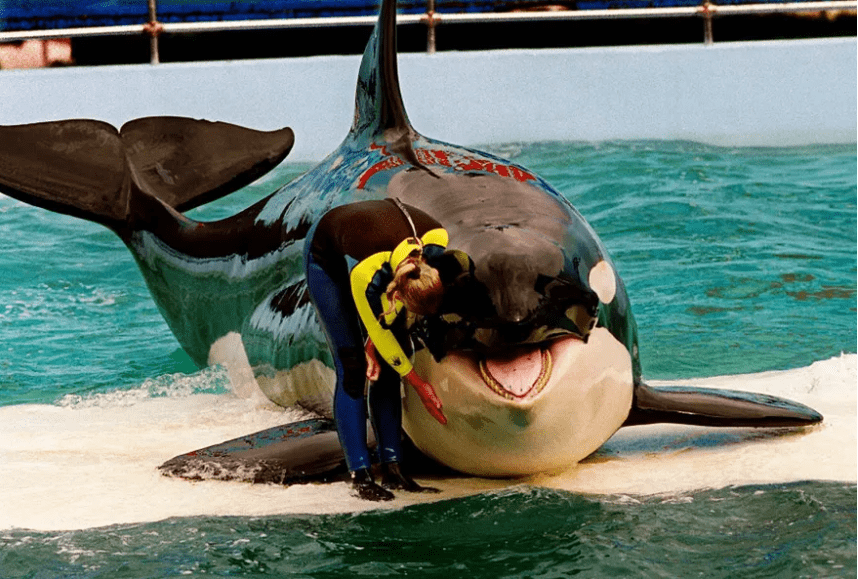

This female whale has lived in Miami Seaquarium, the smallest orca enclosure in North America, for 52 years, performing for large crowds up until her retirement early this year.

Now, there is hope that she will return home. Tokitae, the whale’s name, is being returned by activists to the Pacific Northwest, where she can live out her last days with her family. Her mother is believed to be now in her 90s. She still swims the Salish Sea to help a pod of south-resident killer whales to find salmon.

Her captivity has been described as an anachronism. It is a bridge between a past time when whales could be sold for entertainment and today, where the practice is generally disregarded. The campaign to free her has drawn support from all walks of society, uniting activists, Indigenous groups, and philanthropists in a common cause.

Charles Vinick from the Whale Sanctuary Project, which frees captive whales worldwide, states that “We owe all these captive animals an opportunity to live in an environment as close to their natural environment as we can possibly provide,”

Vinick recalls that whales such as Toki have made millions for their owners and entertained many people. “We owe them a retirement program, a pension … giving them back something like this is the least we can do.”

Her possible release raises profound questions about the past and how to correct them. Is it possible to safely release an animal that has been held so long in captivity into its natural environment? If so, where can she be released?

These answers may help her and other whales around the world. The Whale Sanctuary Project states that more than 3,000 dolphins and whales are still in captivity worldwide, including more than 60 orcas and 300 belugas at aquariums and marine parks.

Lolita Tokitae is Toki’s show business name. For 48 years, Tokitae performed in shows, flipping and lifting trainers in the air.

Her life has not always been easy. Hugo was her tankmate for ten years. He died from a brain aneurysm in 1980 after repeatedly smashing his head into the glass walls.

Toki, or Tokitae for short, is the second-oldest killer whale kept in captivity. Her health has been rocky. Recent independent assessments have documented the effects of an acute illness that struck Toki earlier in the year.

Experts say that despite these issues, she is still in excellent health despite her lengthy captivity. Howard Garrett, a whale researcher and activist for the Orca Network of Whidbey Island who began working on plans to release her in 1995.

“She’s a miracle every day,” says Garrett. “It’s against all odds that she is still alive. I think it’s about her mental health that keeps her physical health in good shape.”

He points out videos that show Toki racing around the pool and doing laps without any trainers. He says, “She’s not withdrawn, neurotic, not the stereotypic behavior that indicates any kind of brain damage associated with being in captivity. She may be a complete outlier in her ability to stay healthy.”

Although efforts to liberate Toki have been ongoing for many decades, they have become more urgent in recent years.

In 2005, southern resident orcas received protection under the Endangered Species Act. This protection was extended to Toki by the National Marine Fisheries Service in 2015. The USDA published a report in 2021 describing how Miami Seaquarium had failed Toki with proper care. This included dirty water in her tank and a lack of shelter from the sun. They also fed her rotten fish, which caused intestinal problems.

In 2021, the Seaquarium was purchased by a new owner who was more open to discussing Toki’s release. A philanthropist called Pritam Singh established a foundation, Friends of Lolita, to help her release. Vinick’s group is currently working with Friends of Lolita to help Toki.

Garrett believes she can be returned to the Pacific. She could still be taken for 10 hours by a comfortable stretcher with fleece from Miami to San Juan Islands, cool water. He also claims that there has never been any harm to whales when moving them over the past 50 years.

If her release is possible, it would be a rare event. Keiko, who played Willy, the Free Willy movie character, has been released in captivity. In the 1990s, she was moved to Oregon and rehabilitated there. After five years in the wild, Keiko returned to Oregon. Toki was 22 when he moved from captivity.

Additionally, participation has been shown by the Lummi Nation of Washington State and other Indigenous communities. The Lummi gave her Sk’aliCh’elh -tenaut the name in 2019. This means she is a member Sk’aliCh’elh – the Salish Sea’s resident orcas family.

“We consider the southern resident killer whales to be our relatives that live under the waves,” says Raynell Morris, a Lummi member who is on the board of the nonprofit Friends of Lolita and a part of Sacred Lands Conservancy. “From the beginning of time we have loved and respected them.”

Morris says that Toki’s story connects to Indigenous people and their own history of displacement: “It’s the connection to how our Indian children were taken away to boarding schools without permission and they were stripped of language, culture and family. And many of those children never returned home. We need to take care of her and bring her home.”

Toki’s future is uncertain. There is an operational plan to bring her back into the Salish Sea. However, Toki would require a lot more space and food for the rest of her life. The Whale Sanctuary Project could place her in a netted enclosure. This is a 100-acre (40-hectare) area in Nova Scotia, where they plan to bring other animals. It follows the same model as a land-based sanctuary for elephants, big cats and great apes.

Another concern is her health, not only her own but also that of her pod. Experts fear that Toki’s infection could spread to southern resident killer whales. This group is already endangered and only 74 of them are currently in captivity.

Some fear that she may not make it through the journey due to her age. If she did, concerns are raised about the impact of a wild environment on a senior whale.

“These are very difficult, ethical and health issues,” he says. “Ethically? Oh, yeah, take her home. But at the risk of her life, that’s a much more difficult question.”

Vinick, however, points to her long survival in one of the smallest tanks in the world. “She is one tough whale,” says Vinick.

She seems to be able to recall her past with her family. In 1996, Toki’s family was recorded by a researcher. Reporters then played the recording to Toki at the Miami Seaquarium. Although she did recognize the calls, it is not clear if her family can still communicate with her.

Toki’s unique situation has no clear answers. However, her advocates will not stop trying to find them.